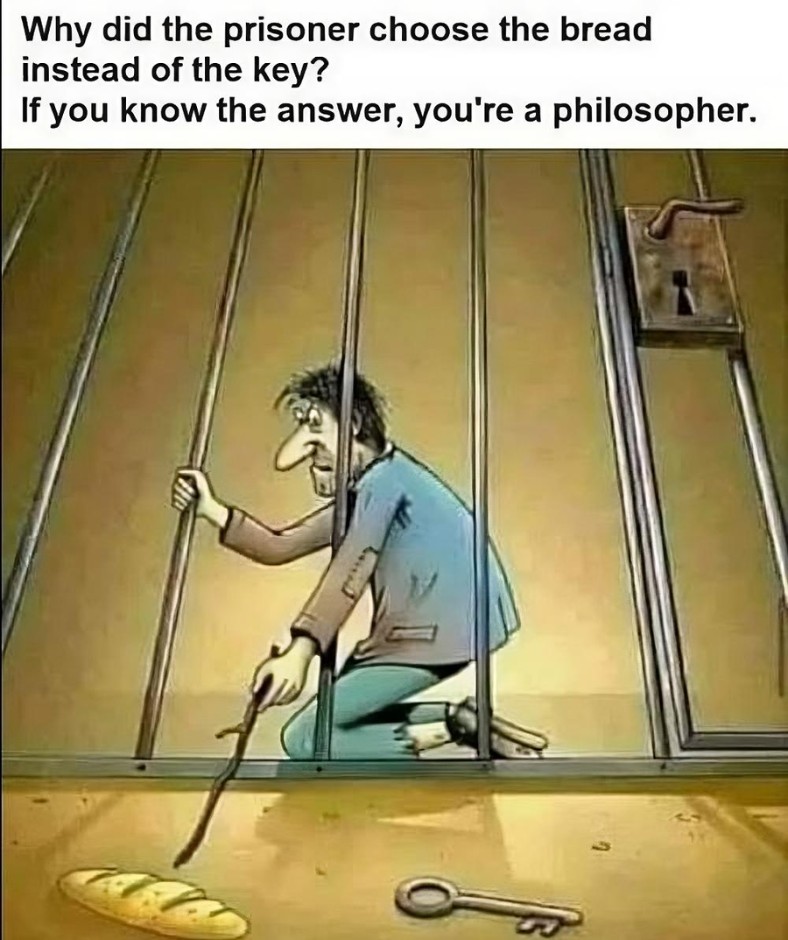

In the thought-provoking parable titled “The Prisoner and the Bread,” a prisoner is presented with a life-altering decision: he must choose between a loaf of bread and a key that could unlock his freedom. Surprisingly, the prisoner chooses the bread, sparking a fascinating philosophical debate about the nature of human instinct and survival. On the surface, the decision might seem baffling—why would someone opt for bread when they could have freedom? But looking closer, this decision holds a deeper significance that speaks to the fundamental aspects of the human experience.

The parable presents a paradox that forces us to confront the values and instincts that guide us in difficult times. On one hand, there is the bread, symbolizing immediate nourishment and survival. On the other hand, there is the key, which symbolizes freedom and escape from captivity. This choice, though seemingly simple, opens up a much larger discussion about human needs, priorities, and the sacrifices we are willing to make to ensure our own survival.

At first glance, the choice between the bread and the key appears to be an easy one. Bread is the basic symbol of sustenance—a necessity for anyone who is starving or in desperate need. The prisoner, facing the harsh reality of confinement, chooses the bread because it provides an immediate solution to a fundamental human need: hunger. When someone is deprived of basic nourishment, it becomes incredibly difficult to think about anything else. In that moment, the prisoner likely saw the bread as a means to stay alive, at least for one more day.

In contrast, the key represents freedom, something that almost any prisoner would crave. The opportunity to unlock the door and leave captivity behind is a powerful concept, symbolizing autonomy and the end of oppression. However, with that freedom comes uncertainty. There are no guarantees of safety or survival once the prisoner escapes. The outside world might hold unknown dangers—lack of food, harsh environments, or the risk of being recaptured. The key provides a way out of the prison, but it does not guarantee that the escape will be successful or that the prisoner will find safety on the other side.

This dilemma was first articulated by the ancient Greek philosopher Plutarch, and it continues to resonate with people today. The core of the dilemma lies in the tension between immediate survival and the possibility of freedom. As Julia insightfully puts it, “Escaping may be the ultimate goal for a prisoner, yet immediate nourishment is an urgent priority.” Julia’s observation reminds us that freedom is an ideal, but basic survival must come first. Without food, the prisoner may not have the strength or energy to make use of that freedom even if he were to escape.

Additionally, bread can hold value beyond just providing sustenance. It could be used as currency—perhaps as a means of bribing guards or trading with others in the prison. This gives the bread an added layer of pragmatism that the key does not have. In a difficult situation, having something tangible like bread that could be exchanged or used to gain favor may be just as valuable as, or even more valuable than, an uncertain escape. By choosing the bread, the prisoner is ensuring that he has something useful in the immediate future, even if it means delaying his chance at freedom.

Examining the philosophical elements of the prisoner’s choice encourages us to rethink our assumptions about freedom, survival, and human priorities. It also challenges us to reflect on our own lives and the choices we make when faced with difficult circumstances. Are we willing to risk everything for an ideal, or do we prioritize immediate needs to ensure our survival? The prisoner’s decision speaks to the importance of evaluating risks and rewards carefully. It underscores that context, available resources, and an honest understanding of our own limitations are critical factors in making difficult choices.

The prisoner’s choice also invites us to consider the emotional and psychological aspects of decision-making under stress. When a person is hungry, tired, and desperate, the promise of freedom may seem less appealing compared to the certainty of a meal. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that basic physiological needs must be met before an individual can focus on higher-level goals such as freedom or self-actualization. In this case, the prisoner’s decision to choose the bread over the key aligns perfectly with this theory—he is prioritizing his most basic needs because, without fulfilling those, nothing else matters.

As Julia beautifully observes, “Regardless of the decision, being mindful of one’s own limitations can be profoundly beneficial.” This statement highlights the importance of recognizing and understanding our own vulnerabilities and the context in which we are making decisions. The prisoner’s choice wasn’t necessarily about lacking the courage or desire for freedom; it was about making a calculated decision based on his current situation and what he needed most in that moment—survival.

Conclusion: A Deeper Look at Survival vs. Freedom

The parable of “The Prisoner and the Bread” offers a compelling exploration of human nature and the ongoing conflict between immediate survival and the longing for freedom. It teaches us that, while freedom is a noble and ultimate goal, it is impossible to pursue without first ensuring that our basic needs are met. The prisoner’s choice underscores the importance of context and the idea that, sometimes, the practical choice is the one that allows us to fight another day.

This story encourages us to reflect on our own lives and consider the choices we make when faced with difficult situations. Are we willing to take risks for something uncertain, or do we ensure that our basic needs are covered first? In the end, the parable reminds us that sometimes, the best path forward is the one that keeps us alive, allowing us the opportunity to pursue greater goals when the time is right. It’s about making choices that serve our immediate needs while also keeping an eye on the future possibilities that may come